Part Two: A new Downing Street

Downing Street:

A new Department for the Prime Minister

We recommend that the Prime Minister, and in turn the country, would be better served by a stronger operation in the form of an Executive Office for the Prime Minister – a new Downing Street department, separate from the Cabinet Office – based around the functions and capabilities needed to support him in leading the government. This new department would get more from the Prime Minister’s leadership, inject discipline across Whitehall and connect the government more effectively with the people it serves.

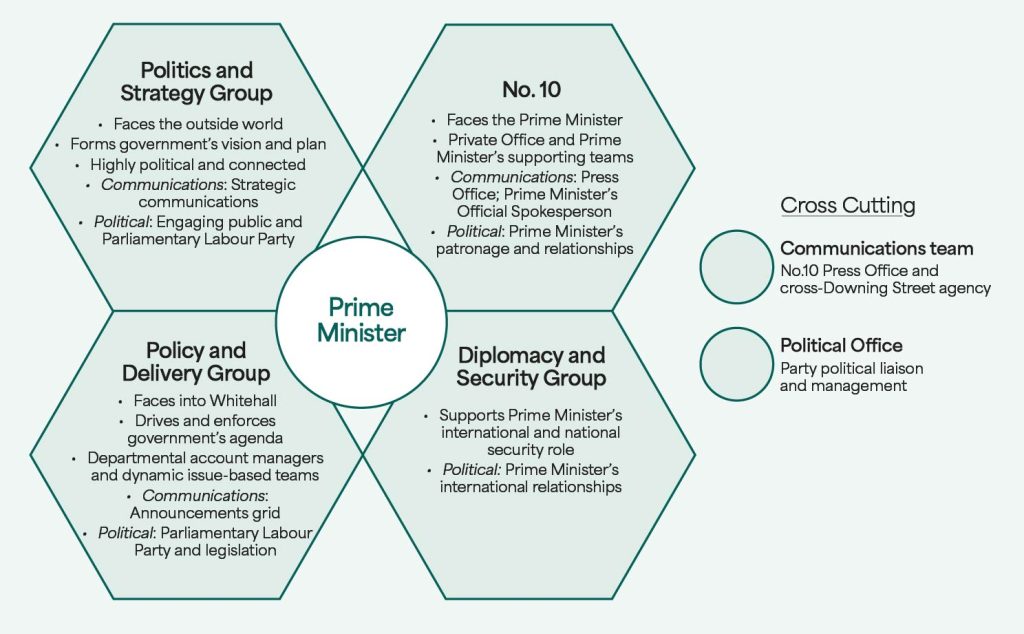

This new and improved Downing Street should have four clear functions, each working in a distinct mode that is vital to supporting this Prime Minister’s leadership:

1

Politics and Strategy Group: A new group focused on the government’s political and longer-term plans. This group faces into the country and listens to the electorate. In doing so, it anticipates the future and meets challenges coming down the track;

2

Policy and Delivery Group: An assertive group to run the Prime Minister’s writ throughout Whitehall, bringing together activities currently dealt with by various parts of the centre;

3

Diplomacy and Security Group: A group to support the Prime Minister in his critical executive function as leader of the country – bringing vital Prime Minister-supporting parts of the National Security Secretariat (NSS) into Downing Street and connecting it to the broader government agenda as domestic and international challenges increasingly overlap;

4

No.10 Private Office: A tightly refocused Prime Minister’s Office at the centre of the Downing Street operation, led by the Private Office. All the staff in this group directly support the Prime Minister and run the functions he needs closest to him.

These four groups are discrete from one another but highly interconnected. On most projects, and on most days, people from each group would be working together in some form or other. They would also be supported by two cross-cutting functions – the Communications Team and the Political Office – which would operate across all four groups.

This new Downing Street is not a new bureaucracy, adding more complexity to the centre. The entire intention is that it should be the opposite: streamlining the centre of government, with the very centre attempting to do less directly itself by setting clearer expectations of what can and should be done elsewhere in Whitehall (and what can and should be stopped altogether). Our approach identifies the essential components of a successful operation for this Prime Minister at this moment, and provides them in the simplest possible arrangement.

There are several advantages to drawing a corporate boundary around this new Downing Street department so that it is no longer an organisation within an organisation (No.10 nested within the broader Cabinet Office) as is the case today. It would eliminate ambiguity about which teams either side of the link door are in the lead on a particular issue. If an issue is for the Prime Minister, then it is handled within Downing Street, and the sub-division of effort is then coordinated under a single leadership team. The new arrangement would also give more firepower to the Prime Minister, including the ability to appoint ministers within the new department to bolster the operation on a day-to-day basis and share some of the load. This would be along the lines of the way David Cameron operated with Oliver Letwin – someone who had the authority to fix problems but who was very clearly operating on behalf of the Prime Minister and not pursuing his own personal ambition. The new department would also be able to set its own processes – including flexibility in recruitment and hiring practices (see below) – without having to contort them into the framework of a Cabinet Office arrangement that has become hobbled by over-bureaucratisation. Lastly, it would also provide much greater clarity in terms of Civil Service leadership, both within the new organisation and projected out into Whitehall and beyond.

Figure 1: Structure of the new Downing Street

This new department would sit at the apex of the UK’s national government, but it would not attempt to do everything itself. It would be a well-networked institution, confident about what only it can do – setting the overall direction for government, based on the Prime Minister’s political programme, and seeing through the delivery of his priorities. It would empower other state actors (Whitehall departments, Secretaries of State, special advisers and Civil Service leadership teams; devolved, regional and local government; agencies and regulators) to play their roles as effectively as possible. It would embody FGF’s core principle of an effective, mission-driven approach: to ‘lead with purpose, and govern in partnership’ 1.

An essential relationship for this new networked department would be, as today, the one that it holds with HM Treasury. This working relationship would need to be particularly close, and recent history shows that government does not work well if it is effectively trying to function with two alternative centres. In keeping with the deliberately narrow remit of this report, we have not looked in detail at potential reforms to the Treasury nor the right balance of powers between it and Downing Street. That said, it might be advantageous to bring HM Treasury’s spending control and decision-making functions alongside Downing Street’s policy and delivery functions – something that was done most effectively in the past when Jeremy Heywood was Cabinet Secretary and his Cabinet Secretariat worked with the Treasury team to set one strategic approach under the joint direction set by the then Prime Minister and Chancellor. One way of achieving this would be to have the Chief Secretary to the Treasury report to both the Chancellor of the Exchequer and the Prime Minister (who is, after all, also First Lord of the Treasury) as a joint minister. This would not remove spending control or decision-making powers from the Treasury, nor decouple those powers from its wider stewardship of the economy, but it would mean a more formal, ‘hard’ link between Downing Street and the Treasury in this area, and give Downing Street’s Policy and Delivery Group more leverage over Whitehall departments as a result.

The new department would be led by a seven-person leadership team, a tight-knit group consisting of the Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff, Director of Communications, Principal Private Secretary (PPS), Chief Policy and Delivery Adviser, National Security Adviser (NSA), Chief Politics and Strategy Adviser and a new Chief Operating Officer (COO). While several of these positions already exist (Chief of Staff, PPS, NSA and Director of Communications) some would be new or different to those which exist today:

1

Chief Operating Officer (COO): Would provide corporate leadership to Downing Street and lead the work to establish the new department’s working culture. Their responsibility would be to ensure that the new department is run as well as possible. The COO would also lead the new recruitment model (see below), oversee the establishment of the new department’s processes and capabilities, and foster an excellent culture that brings the department together. This is a full-time job: it should not be done off the side of someone’s desk, and nor should the COO be getting involved in policy work.

2

Chief Policy and Delivery Adviser: An incisive, politically-attuned individual with the knowledge, experience and stature to lead the Policy and Delivery Group from the top and effectively exercise authority over Whitehall. This post could be held by either a civil servant or a political appointee: if filled by a senior civil servant, then they should be flanked by more party political experienced deputies, and vice versa.

3

Chief Politics and Strategy Adviser: A well-connected, highly political individual responsible for coordinating and managing the work of the Politics and Strategy Group and leading medium and longer-term thinking across Downing Street. They should be an empowering leader, capable of convening a wide range of thinkers and practitioners with the most innovative and valuable ideas, real-world experience and actionable insights. Their leadership mode should not be one of command and control, and staffing arrangements within their group should be as flexible and porous as possible, including short-term secondments or ‘tours of duty’ (subject to high standards of propriety).

If Downing Street is to be a new government department, then a Permanent Secretary would need to be appointed. That role could effectively be held by either the PPS, the COO, or the Chief Policy and Delivery Adviser (if a civil service appointment) – depending on who was best placed. But the group as a whole should reflect the different leadership experience and skills the Prime Minister needs. When his top team works well, it is not just a group of individuals but a genuinely collective effort: ensuring clarity of shared purpose, fostering and modelling the behaviours and conduct that should hold throughout the organisation, and creating an environment which optimises for the Prime Minister to make the best possible decisions.

This is not to say the team should always be in total agreement with one another nor settle for compromise on the median position between the seven leaders: high-functioning leadership teams allow for robust challenge and disagreement internally, before collectively owning final decisions and then presenting a united front externally. And if the leadership team cannot reach agreement, then it is for the Prime Minister to arbitrate. His is the power to make the ultimate decision which the leadership team then put into action throughout Downing Street and beyond.

Aerial image of Downing Street, London SW1

These structural changes will only have their intended impact if they are accompanied by a positive, purpose-driven culture of excellence. The new leadership team should institute a new set of shared cultural values, co-designed and developed with the wider workforce and modelled by everyone. Downing Street should establish and promote a ‘one team’ approach alongside rigorous levels of accountability.

Calling this new operation ‘Downing Street’ allows it to make full use of the physical estate on that road and to do so more intentionally. The Prime Minister’s Office itself would still be physically within 10 Downing Street (and known as ‘No.10’), but the other three groups could be based across Numbers 9, 11 and 12 Downing Street, Kent’s Treasury and potentially, over time, in parts of the Downing Street side of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office buildings. This is also about rationalising the numbers of staff working at the very centre. In 2014, the Cabinet Office employed around 1,990 full‑time staff. By 2024, this had grown to 6,315 full‑time staff 2. There is limited public information available about the exact number people working to the Prime Minister across both No.10 and the relevant secretariats and units in the Cabinet Office, but the IfG’s Commission on the Centre of Government showed how the No.10 headcount alone had risen to 350 by early 2024, five times what it had been under Margaret Thatcher and still over 100 people more than worked in Tony Blair’s No.10 when it was at its largest3.

The idea of a Prime Minister’s Executive Office is not a radical one: in fact, the UK is unusual in not having a dedicated structure to support the head of government across policy, strategy and delivery. Across many comparable democracies – including Australia, Canada and Sweden – the presence of a clearly defined Prime Minister’s Executive Office is seen as essential to effective government. Australia maintains a dual structure, with the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet offering whole-of-government advice grounded in the Civil Service, sitting alongside the Prime Minister’s Office, a politically appointed team that offers partisan strategy and media support. Canada and Sweden follow similar models, combining political responsiveness with institutional stability 4. None of these models is perfect, and it would not be possible or advisable to try to import wholesale other countries’ arrangements and expect them to work for the specific context of the UK’s Labour government in 2025 – but they do show that a structure along the lines we are proposing is eminently achievable and operational elsewhere.

Below we set out in more detail how this new Downing Street would work in practice: the culture of the new organisation, the profile and roles of each of its four constituent groups, how communications and political functions could be embedded throughout, and some proposals for how to recruit and retain the very best talent into this new set-up for the centre of government.

Culture in the new Downing Street

Structural change alone won’t deliver the level of transformation that is needed at the centre of government. The leadership team of the new Downing Street must dedicate an equal amount of time and attention to the cultural and behavioural shift necessary to foster an enabling and empowering environment in pursuit of excellence. No one is too busy or too important to lead well.

Culture is not spoken into existence but emerges from the behaviour and interactions of groups of people. The leadership team needs to understand the conditions and ingredients that allow a high-performance and positive working culture to develop.

Downing Street should be a high-performing organisation, underpinned by a culture that brings out the best in all its people. This culture should be built around three core principles:

- Clarity of purpose. This is crucial to shifting from the current reactive model to one in which Downing Street makes its own weather. There should be a clear shared ‘north star’: a unifying sense of direction developed by the leadership team together with the wider staff and agreed by the Prime Minister. The leadership team should give staff as full and open a view from the top as possible, to improve people’s awareness of, and to enhance people’s trust and buy-in for, the overall programme.

- Clarity of roles and responsibilities. The new Downing Street culture should be one which establishes clear ownership of projects, activities or policy areas by a named person, with minimal overlap or interference. This starts with clear job descriptions, and should contribute both to the system working as effectively as it can and to the intrinsic motivation of staff. This should create and sustain the conditions for good people to do their best work through ‘context, not control’, via three ingredients of authority, autonomy and accountability.

- Great place to work. Downing Street should be a place that brings out the best in those who work there and attracts the brightest talent from across the country. The centre of government has its own unique pressures and it is important to purposefully create a great culture for people to work in. Cultural values should be co-developed and modelled by everyone across the four groups, fostering a sense of ‘one team’ through collaboration, support and connection, openness and transparency, candour and inclusion while ensuring accountability through high standards, high challenge and high support.

These principles should then be made tangible through a range of different mechanisms within the new department, from recruitment to training and development, from setting specific metrics, assigning clear accountability for them and evaluating progress including through staff surveys, and from a system of regular and continual feedback to one of recognition and celebration of individual and team successes.

The four groups in the new Downing Street

1. Politics and Strategy Group

Primary purpose: to incubate fresh thinking about some of the thorniest challenges facing the country and the overarching long-term agenda of the government; and to devise and develop practical strategies to tackle these challenges.

For half a century, governments of different stripes saw the benefits of having some form of strategic capability at the centre 5. Yet this function has now been lacking from the Prime Minister’s Office for several years and its absence is keenly felt. In an era of both relentless information flow and growing polarisation, it is more important than ever to have a protected space at the heart of government to think slowly and long-term.

This is something which Keir Starmer has specifically argued for, both in opposition when criticising what he termed ‘sticking plaster politics’ and in government as he has advocated ‘fixing the foundations’ and taking a mission-driven approach to deliver a ‘decade of national renewal’. Such an approach necessitates carving out the space to develop and prioritise long-term, audacious ambitions. It also means being alive to the risk that without this dedicated capacity to think differently, short-term crisis response will often crowd out planning ahead for future generations – a capability which is arguably more urgent to get right.

We recommend the creation of a new Politics and Strategy Group (PSG) to set the overarching, long-term agenda for the government. This should be the hub within the new Downing Street for more considered, anticipatory thinking and for conducting and responding to meaningful public engagement. It should be defined both by this mode of working and by operating on a time horizon of the next three months at a minimum (and at times over the next decade or beyond). PSG should work closely with the other groups in the new Downing Street model and draw together all the different strands of the organisation into a single plan focused on the bigger picture.

The PSG’s focus on ‘strategy’ should not be confused with being aloof or overly academic; the group should not be driven by producing theory, but ruthlessly pragmatic and hands-on in its approach. Carrying out its role well, the PSG should confer a strategic advantage to the centre of government and improve the productivity of Downing Street as a whole. It should be able to overcome the longstanding barriers to delivering results in Whitehall – be that bureaucratic complexity, or long lists of reasons as to why things cannot be done (or at least cannot be done as quickly as the public would want). It should also help to avoid the current problem where almost everyone in the centre of government has to try to switch between focusing on the immediate and lifting their head up to the horizon, a tension which hampers effectiveness.

A key characteristic of PSG should be its openness to external experience and insight. It should face outwards: listening, connecting and partnering with a range of stakeholders – from local and regional government and other arms of the state; to backbench MPs and the insights gathered from their constituencies; to think tanks, trade unions and wider, civil society organisations; to the broadest definition of private sector organisations; and to the public themselves. Staff in this group should regularly get out of Whitehall and interact with sectors, stakeholders and members of the public and bring insight back. Key traits for people working in PSG should be a professional approach to relationship management, a culture of curiosity and open-mindedness, and a confidence that government can orchestrate collective efforts from an array of different actors.

The PSG should be the home in Downing Street for specific capabilities such as future scenario forecasting – not attempting to predict the future, but clarifying choices by working out plausible outcomes – and sophisticated data analysis. Their research focus should be on qualitative public opinion data from focus groups and quantitative data supported by an expanded version of the 10 Downing Street Data Science team (10DS). A new 10DS should combine its original function as envisaged when it was established in 2020 – as a set of expert outsiders providing critical data input to Downing Street on specific questions – with the addition of wider psephological and attitudinal work to inform the government’s overall programme.

Importantly, PSG should have an innovative, entrepreneurial culture in the best traditions of government ‘start up’ units such as 10DS, the Government Digital Service and the Behavioural Insights Team. Small, dedicated teams within PSG should be tasked with incubating fresh thinking about some of the thorniest challenges facing the country, be that the implications of AI, the need for new models of public service provision or the development of new forms of public engagement. These teams should have the political cover to be comfortable with risk-taking in the knowledge that some of their work may ultimately fall away in the pursuit of ideas that can be genuinely transformative. That risk-taking should also extend to stretching the government’s current set of ambitions so as to consider what might be possible and necessary much further into the future. For the current government, that would mean tasking PSG to think about identifying obstacles (or potential catalysts) to extending its political programme further still, to think about what the second half of an ambitious, progressive ‘decade of national renewal’ might look like and how to get there.

PSG should handle AI both as a major public policy issue and as a technological development that can have a profound impact on how government operates. There are countless, often competing, predictions about AI’s future, but there is a consensus this is a type of technology that will have broad-ranging impacts on society and the economy, and may continue to be marked by surprising developments or accelerations. Downing Street needs to grasp AI, not in terms of individual policies or technologies – which should remain the remit of the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology – but in terms of forming a view as to how government works on AI in the round.

The physical working environment for PSG should be open plan and separated from the speed of day-to-day response required in much of the rest of Downing Street (so within one of the other buildings on the Downing Street estate rather than No.10 itself). The group would get its licence to operate not from physical proximity to the Prime Minister within No.10, but from high-quality commissioning from the leadership team and from dedicated, regular and protected time with the Prime Minister (for example, a regular 90-minute PSG-Prime Minister meeting to cover a small number of select strategic issues, well-prepared in advance and discussed in detail).

2. Policy and Delivery Group

Primary purpose: To drive and enforce the agenda of the Prime Minister across government.

A refreshed Policy and Delivery Group (PDG) would grip government business, coordinate activity across departments, monitor implementation of key policies and trouble-shoot where necessary. This group should be a nexus of high-level politically-attuned problem solving, close to the Prime Minister, advising him and exercising his authority. Where PSG faces out to the country and other tiers of government, PDG should face into Whitehall, driving and enforcing the agenda of the Prime Minister across government.

PDG should make clear recommendations to the Prime Minister on the basis of evidence, and it should carry out three essential functions: policy coordination, delivery and monitoring, and navigating the government’s programme through Parliament. By drawing together Downing Street’s policymaking and monitoring functions, the new PDG should enable the centre of government to know how policy has been developed in Whitehall departments and how those departments are getting on with delivering it. It should also be the part of the Downing Street system that troubleshoots particularly knotty policy problems.

The heart of this new group should be the very best elements of the No.10 Policy Unit since its establishment by Harold Wilson over 50 years ago. That means acting as the Prime Minister’s ‘eyes and ears in Whitehall’, as Wilson instructed the Unit’s first head, Bernard Donoughue, and being – in the words of Sarah Hogg, who was the Unit’s first female leader, from 1990-95 – the ‘grit and oil in the government machine’6. Every Prime Minister since Wilson has retained the Policy Unit in some form or other, reshaping it to their own needs with a greater or lesser degree of intentionality, and the new Downing Street PDG should take the best of what the Unit has achieved over that time and adapt it to suit the needs of the current Prime Minister and the specific challenges of the current moment. In particular, that means that PDG should simplify policy and delivery roles and escalation routes at the centre of government so everyone within the system is clear about who to go to and when – with accountability crystal clear, and collaboration and information-sharing baked into the system (while information-hoarding is demonstrably not tolerated).

Achieving that greater simplicity would require bringing into Downing Street – and rationalising – several functions that currently sit in the Cabinet Office. This has already happened with the Missions Delivery Unit (MDU) but the same logic could also be applied to elements of Economic and Domestic Secretariat (EDS). The MDU was too far removed from No.10 when proximity to power is undeniably an indicator of influence. Bringing the MDU’s functions out of the basement of 70 Whitehall and into the Downing Street perimeter should more strongly connect it to power and influence – politically and administratively – and make it much more effective in driving the Prime Minister’s priorities and the national missions. Similarly, Downing Street should bring ‘in house’ the model of EDS when it has operated at its best in the past: a small team who can be on top of policy development and delivery in Whitehall and across progress and departmental dynamics. Every department should know their named desk officer in this model. PDG should hold and exercise important levers over departments, such as securing collective cabinet agreement on policy issues via the cabinet committee ‘write round’ process.

In this new arrangement, the Cabinet Secretary would retain responsibility for the principles of cabinet government and the constitutional aspects of the Secretariat but would not be responsible for driving day-to-day progress on behalf of the Prime Minister. This should liberate the Cabinet Secretary to focus on wider leadership, people management, capability-building and reform across the Civil Service (similar to how responsibilities were divided when Jeremy Heywood was the Permanent Secretary of No.10 and Gus O’Donnell was the Cabinet Secretary). Our working assumption is that the Cabinet Secretary would continue to be the manager of the most senior civil servants in Downing Street and on an issue-by-issue basis could play in and out as suits him and the Prime Minister.

Consistent with the focus of this report, we have not ventured into looking at wider Cabinet Office reform, which has been well covered by other recent reports such as IfG’s Commission on the Centre of Government7. Alongside this new Downing Street model, the Cabinet Office would continue to have a critical role. That is consistent with, and complementary to, a standalone Downing Street department, and providing greater clarity of roles should also help the Cabinet Office itself. Currently it tries to both drive the Prime Minister’s agenda forward and house several vital cross-government functions; being much more intentional about what sits within Downing Street and what remains within Cabinet Office will allow the latter to carry out its cross-government functions in a more strategic and focused way.

(i) Policy coordination

This group coordinates policy decisions and communicates them out to the rest of Whitehall. This would be reflected in the new PDG operating on an account management model, with named desk officers acting as lead contacts for one or more Whitehall departments. Each desk officer should know the plan for a specific piece of work or resolving an issue and how it fits within a broader government programme or mission, meaning there is clearer ownership of an issue internally within the centre. They should also work closely with both Private Office and the Communications Team to grip the daily events and issues that require a quick, firefighting response but do not necessitate standing up a full-blown crisis team (as below). This sort of model has been commonplace in the past.

Alongside the desk officers would sit a small ‘surge pool’ who have specialist skills – for example, economists, analysts, planners, AI and predictive analytics experts, specialists in digital marketing or campaign communications – who can be deployed to support policy sprints on difficult issues where additional capacity is needed. This group must have a clear lane boundary with the PDG delivery and monitoring function (see below): while collaborating with them to ensure decisions can be followed through, they do not ‘chase’ downstream implementation by departments.

As well as this surge pool, PDG should have the capability to stand up dynamic project teams to manage pressing or contentious issues or crises that require Prime Ministerial involvement and a cross-departmental response. PDG should be able to anticipate and optimise for this type of work, bringing the relevant people together at speed, formulating a plan and then using the power of the centre to steer action and delivery of that plan. Crucially, these temporary teams should be made up of people working in the relevant departments or agencies who work together for a time and then the unit or project should be stood down when the crisis or urgent priority has passed. The model is convening, not taking over.

(ii) Delivery and monitoring

PDG should be the part of Downing Street that gives the Prime Minister line of sight to the delivery of his government’s programme, ensuring he can hold both ministers and officials to account. This should be a combination of insight – close, detailed analysis of government activity to deliver an agreed list of the Prime Minister’s personal priorities – and accountability from judicious use of Prime Ministerial time, power and patronage.

To ensure that priority policy is delivered, PDG must be able to work collaboratively with Whitehall departments while being ready and able to tell hard truths. The existence of a central Downing Street delivery function should not mean disempowering Whitehall departments, who should remain in control of delivering their responsibilities; the PDG’s role is to zero in on the Prime Minister’s policy priorities and unblock areas of major political or implementation risk – it should be tightly connected to political need.

PDG’s delivery function should learn from what worked before in the previous Labour government’s Delivery Unit8 and the Coalition government’s Implementation Unit9, including undertaking ‘deep dives’ into specific areas of policy to ensure delivery, unblock problems and hold departments to account. The new PDG should also make systematic and effective use of data analytics to agree metrics, set milestones with Secretaries of State and monitor performance – strongly supported by the 10DS function within PSG (but where the data is led by the politics, rather than the other way around).

(iii) Parliamentary liaison

PDG would also have a responsibility, working with the cross-cutting Political Office (see below), for ensuring the government’s policy agenda can be delivered through Parliament, and that the setting and implementation of that agenda is grounded in parliamentary reality.

This requires serious capacity and expertise to manage controversial legislation from the very centre of government and we would recommend re-establishing a Director of Legislative Affairs within Downing Street, heading up a small legislative affairs team, which sits within PDG and works hand-in-hand with the Political Office. These two units should work together to combine effective listening and engagement with the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) with expert procedural knowledge of parliament and deep political sensitivity. This part of PDG should also work with the Whips’ Office to take the temperature of the PLP, identify pressure points and turn backbench concerns into early intelligence and advice to the Prime Minister and his top team.

The key to the PDG working effectively is that all three of these functions clearly have the authority of the Prime Minister – acknowledging the existential importance of effective delivery to trust in government – and that they cohere into a single process, sitting under a single leader: the Chief Policy and Delivery Adviser. Within the team there should be clear lanes but a culture of constant collaboration – delivering the government’s mandate is a shared enterprise – and this should be set from the very top.

It would also be important to appropriately calibrate the interaction with the Private Office function within No.10 (see below). While PDG should have its own proximity to the Prime Minister and should be responsible for making recommendations to him on the basis of evidence, those recommendations would need to pass through the Private Office, and the Private Office alone would then record and transmit the Prime Minister’s ultimate decision. In the ordinary course of business, the Prime Minister’s Private Office would speak to Secretaries of States’ Private Offices on behalf of their principals, while PDG would be the conduit for the policy and delivery work of departments into, and out from, the centre.

3. Diplomacy and Security Group

Primary purpose: To support the Prime Minister in his personal leadership of international, European and security issues

The Diplomacy and Security Group should support the Prime Minister on the international stage and advise on national security, and should be led by the National Security Adviser (NSA). This function is currently clearly defined under the National Security Secretariat (NSS), and most of its existing functions should be moved from being corporately located within the Cabinet Office to falling within the perimeter of Downing Street.10

While other parts of the Downing Street operation will be engaged in aspects of policy, delivery and strategy that have a strong international dimension – not least as international and domestic policy and politics become increasingly intertwined in the modern world – discrete additional capacity to lead on diplomacy and security will continue to be vital for the Prime Minister. The specific skillsets, experience and capabilities of this group can then be deployed across the Downing Street organisation as needed, particularly on areas where domestic and international policy work clearly overlaps, such as trade or immigration.

4. Prime Minister's Office ('No. 10')

Primary purpose: To act as the authoritative voice of the Prime Minister in Whitehall

The Prime Minister’s Office is the group whose specific role is to serve the Prime Minister directly and support him to make decisions. They are the only set of staff working within the Prime Minister’s home and workplace of No.10 Downing Street.

The core of the Prime Minister’s Office is the Private Office. The new Downing Street arrangement should enable the Private Office to operate at its most effective, with clear lanes so that it is not being pulled into policy, delivery or strategy work which is best done elsewhere. This in turn should ensure the Private Office can optimise for the best Prime Ministerial decision-making.

This isn’t a new function; it is a deliberate return to this part of the centre of government operating at its very best. That means acknowledging that the Prime Minister’s Private Office possesses unrivalled opportunities for access and influence and makes judicious use of the power that entails. It also means recognising that successful Private Office operations in the past have always carved out distinctive roles for those serving the Prime Minister, avoiding overlapping responsibilities and that these clear lanes need to be continuously enforced by the PPS.

The Private Office should be the authoritative voice of the Prime Minister in Whitehall: the only group with the authority to issue a definitive decision or settled view on an issue from the Prime Minister, and there must be an acknowledgement across the rest of the system that a decision is only a decision once it has been communicated by the Private Office. There should be no ambiguity or time lost ‘interpreting’ decisions – people elsewhere in Whitehall should know that what they have been told by the Private Office is what the Prime Minister thinks (not what an amorphous ‘No.10’ thinks).

Sitting alongside the Private Office within this group would be key elements of the cross-cutting communications and political functions (see below), as well as other existing teams that the Prime Minister needs to have immediately to hand, such as the Duty Clerks.

The Prime Minister’s Office should be led on the Civil Service side by the Principal Private Secretary and on the political side by the Chief of Staff, working in lockstep with one another as part of the wider Downing Street leadership team. It should be staffed by a diverse cadre of the most impressive civil servants across Whitehall, rotating in and out on a sufficiently planned and strategic basis that institutional memory is maintained. A ‘tour’ of the No.10 Private Office should be seen as a sign of serious ambition, and as something requiring specialist skills, with departments sending their best people into the centre, and rewarding them when they return.

Transformation of this group within our new model is not driven by radically new structures or roles, but rather from the wider reorganisation of Downing Street permitting the Prime Minister’s Office to have a singular clarity of purpose. This should enable No.10 to focus exclusively on the Prime Minister compared to the broader focuses of the other three groups.

Cross-cutting functions in the new Downing Street

1. Communications Team

Communication considerations need to run through all four groups, and so as now there should be a cross-cutting Communications Team, led by the Director of Communications who would sit on the Downing Street leadership team.

Different communications functions would then be co-located with different groups, depending on the rhythm of their work. The Director of Communications, the Prime Minister’s Official Spokesperson (PMOS) and a lean press office managing the communications grid – which should be much more strategic in nature and driven from the centre – should all sit in the Prime Minister’s Office in No.10. This central press office should retain the in-depth policy specialisms that its current staff have today. Meanwhile a more strategic communications function would interact with the other three groups, acting in practice like an in-house campaigns or agency function, with teams being stood up and ‘seconded’ into the other parts of Downing Street to work on specific tasks (and in turn docking in with similar functions across Whitehall and other public bodies to amplify the effectiveness of centrally-designed government campaigns).

In practice, this could mean working with PSG on multi-year behaviour change or influencing campaigns rooted in public opinion; with the 10DS function on social listening work to inform government messaging and use of different channels; with PDG to communicate the purpose and impact of major policy initiatives aligned with the Prime Minister’s personal priorities, or with DSG on the communication of major international diplomatic or national security conferences.

As with PDG for policy, the Communications Team in Downing Street needs to have strong links to, and grip over, communications activities in the rest of Whitehall. The politically-appointed Director of Communications should work hand-in-hand with the government’s new Permanent Secretary Director of Communications11 to an agreed and shared strategy, with a greater grip on departmental marketing spend and procurement and a strategic approach to deploying gov.uk as a communications tool. The centre should be able to actively direct departmental Directors of Communications (at present they are task managed by departmental permanent secretaries, who are rarely communications experts).

This should enable the centre of government’s communications function to be much more strategic, proactive and prioritised: picking a small number of core campaign messages to push from the centre, and then deploying those again and again in different ways, across different platforms and to different people. This should allow space for innovation and experimentation, reflecting that the ways in which news is created and consumed are changing rapidly, so government should complement its traditional media approach with a greater focus on new media and different methods for landing its messages with an attention-poor and generally distrustful public. This will require a major mindset shift within government, which still tends to be biased towards traditional media rather than the new, digital channels by which most people now consume their news. It also means thinking strategically about the power of the Prime Minister’s direct communications to the public, his brand and that of the government as a whole.

2. Political Office

Similar to the cross-cutting communications function, a well-resourced Political Office should play a vital role in managing the flow of politics throughout Downing Street. Under this new setup, the Political Office would work closely with the other groups to ensure political management is integrated across all activity and decision-making, which is essential to the smooth and more effective operation of government. In particular, that means the ability to operate on all of the rhythms required: capable of reacting to immediate political crises that emerge and injecting political considerations into day-to-day responses to events; ensuring that the governing party’s political programme is factored into PDG’s managing of the Whitehall machine to deliver the Prime Minister’s policy priorities; and working with PSG to ensure long-term strategic planning always has politics at its core.

The Political Office should be staffed by a dynamic mix of seasoned political hands and diverse, emerging talent, led by a Political Director who reports to the Chief of Staff. The office should face outwards – across Parliament, Whitehall, and the Labour Party12 – ensuring all three are in sync. To do this the team should spend as much time outside of Downing Street as inside, building strong relationships with MPs, the Whips’ Office, PLP Office, and party headquarters and feeding insights back into the centre.

In its work the Political Office should aim to:

- Map and cultivate wider political networks. This should involve systematic analysis of existing and potential political connections to build the most comprehensive ecosystem of supportive political actors – in their broadest sense – to build a coalition to engage in the government’s programme.

- Bring party political insight back into Downing Street. The team should gauge the dynamics among the government’s political stakeholders – MPs, peers, devolved leaders, mayors, local government leaders and beyond – and use that to inform Downing Street strategy and tactics.

- Get the best from the political ecosystem. The Downing Street political team should work with the Whips’ Office, PLP Office and others to identify and nurture the next generation of diverse, progressive political talent; to reward loyalty, hard work and ingenuity from within the political party; and to strategically and systematically build an ecosystem of supporters and outriders who can create a permissive environment for the government’s political programme.

In practice, within the new Downing Street model this could mean the Political Office working closely with PSG to ensure the party political angle is factored into long-term strategy and planning; embedding political management into PDG’s coordination and delivery of new and existing policy programmes; adding political considerations to submissions to the Prime Minister or upcoming planned events and visits; or working with the Communications Team when developing and disseminating long-term campaign messaging or short-term reactions to external events.

Appointments in the new Downing Street

A fundamental shift in the approach to recruitment

Downing Street should be able to attract, appoint and retain the very best people in the country for the roles that it is looking to fill. Getting the best talent into the operation is an essential precursor to everything else we recommend in this report, and it becomes self-fulfilling: the more high quality people work in the building, the more talented outsiders want to come to work there.

Yet as things stand, recruitment into No.10 is not transparent and not necessarily best in class. The Prime Minister – and in turn the country – would be better served by a clearer, more transparent system geared towards attracting and retaining the very best, most diverse talent possible.

Getting to that position would be much easier if, as we propose, Downing Street becomes a standalone department, able to operate its own bespoke model of appointment and management – including autonomously setting its own policies around hierarchy and remuneration. This new model should have clear principles around propriety and accountability, and should be both tougher and more transparent than the status quo. Under the new model, roles should be clear and distinct from one another; they should be advertised by default; and once people are in post they should be held accountable for their performance while the in-house training for continuous improvement should be excellent.

This will only happen if the task of finding and hiring people is rightly treated as an important job in and of itself. The new Downing Street should create a world-class recruitment and HR function which takes the business of hiring the right people in, and getting the best out of them, much more seriously. A dedicated function should support the Downing Street leadership team to realise this new model in practice.

Hiring managers within Downing Street should be tasked with the brief “hire someone better than you”, recruiting to task and priority with a flexible approach free of unnecessary bureaucracy so as to attract the best possible external talent without opportunity cost to their wider career. To reinforce the simplicity and clarity which we have argued for throughout this report, all job descriptions within the new Downing Street operation must be explicit and not overlapping; it needs to be clear where one role stops and another begins. Jobs need to be more clearly defined, based on experience about what works well in practice.

Overcoming the blockers to a new model of recruitment

Putting in place this new kind of recruitment and management model is easier than often thought. The rules governing direct appointments within and into government – be that in statute via the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 (CRAG 2010) 13 or within the Civil Service Commission principles 14 – are more permissive than often assumed or deployed in practice. There are examples of different types of contract being used to recruit different types of workforce in recent history, ranging from the 2012 Olympics to the Government Digital Service or the AI Security Institute.

Whether someone is a Civil Service or political appointee to Downing Street should not – and even under the current rules, does not need to – determine whether they can do the non-party political work the Prime Minister needs in government. While it is right that politically-appointed Special Advisers (SpAds) cannot manage the careers of permanent civil servants, they absolutely can give them direction and set tasks, and they can chair meetings or lead projects if that is what the Prime Minister wants them to do provided the accountabilities are clear.

We recommend that the new Downing Street should move to hiring people on a single employment contract, which allows the department to appoint the best person to any given job, irrespective of background. Formally, this would involve appointing people through two different routes:

- If appointing someone who is already a civil servant to a role in the centre, Downing Street should make use of the Civil Service Commission’s ‘appointment-by-exception’ provisions, where helpful. This would enable Downing Street to use its discretion to pick the best people from across Whitehall. To make the process robust and transparent, Downing Street should formalise this model via an agreement with the Civil Service Commission.

- If appointing someone external to the Civil Service, Downing Street should class them as SpAds under CRAG 2010. In doing so, it is worth emphasising that SpAds are classed as political appointments because the person who appoints them is political (i.e. a minister), not because they themselves are carrying out party political activities.

Whichever of these two routes is used to recruit, the successful applicant would then be appointed on the basis of the new, single Downing Street employment contract. This would involve setting a very clear description of what the job is that someone is there to do and where the boundaries are, and ensuring this is underpinned by the enhanced recruitment principles and transparency regime set out above – enforced by the new COO and dedicated people lead.

The new Downing Street could choose to designate certain SpAd roles within the organisation as specifically party political – those who need to work with Party Headquarters or engage in political campaigning; and who must withdraw from government activity at election time – and in doing so make it much clearer where other SpAd roles are non-party political and to distinguish between fixed term appointments – which could be tied to a parliamentary cycle – and permanent ones. This would be clearer and simpler than the current contorted direct appointments. It would be essential to hold these roles to high standards of propriety and be open and transparent about how resources were being spent to protect against any perception of impropriety. It would be easier to put such obligations on the face of an employment contract.