In a series of reports on British public opinion published in July 2025, a theory of power is visible which appears to be widely held across the population.1

Synthesising the findings, along with related research, that theory emerges as something like this:

Everything is expensive. Nothing works. The people who are supposedly in charge are either useless or just don’t care. They say what they think we want to hear, but really, they just help their mates, and themselves. They don’t play by the rules, so why should we?

This is in many respects unfair, but it springs from real disempowerment. To understand how to challenge this theory, we need to understand what drives it.

According to More in Common, ‘More than one third of adults say that citizens’ actions or choices have little to no influence on how society functions.’2

One controversial manifestation of this is the taking-over of hotels to house asylum seekers, but lack of consultation on this particular issue symbolises a much broader sense of disempowerment. The fate of these ‘crumbling seaside palaces’ is seen to mirror ‘the decline of the towns themselves’.3 Hotels are frequently closed with little warning, creating ‘a damaging sense of community powerlessness’: another possession taken away.4

A report by British Future and the Belong Network found ‘People felt that their needs were not being met, and their voices not being heard, in the context of the cost-of-living crisis, housing shortages and pressures on the NHS. Social and economic factors were exacerbating grievances towards out-groups.’5

It is unsurprising that ‘87 percent of Britons across all parties [have] either not very much trust in politicians or none at all’.6 These feelings are stronger where economic disadvantage is higher: ‘72 percent of those who nowadays are “struggling” on their household income almost never trust politicians to tell the truth, compared with 49 percent living “comfortably”.’7

But many of us feel disempowered not just as citizens, but as customers, and as employees – power relationships which tend to take up rather more of our time.

Alongside immigration, the most pervasive driver of disempowerment indicated in recent polling is the impact of rising prices. A third of respondents report ‘“finding it hard” to get by on their current household income’.8 More in Common reports that ‘Among many Britons there is a feeling that they do not have control over their own lives and that they could be thrown off course by the next energy bill rise or interest rate hike… Britons worry about not knowing what price hikes might be round the corner, particularly given the volatility and unpredictability of food and energy price rises in recent years.’9 This induces a feeling of being ‘almost disposable. Pushed to the side in favour of others.’10 The primary concerns are the costs of housing, transport, food and energy.

Part of the loss of power experienced in deindustrialised areas springs from the disappearance of relatively secure, decently paid, respected work of clear importance to the country – and the amenities that went with it. The old employers have been replaced with less rooted, sometimes multinational companies that ‘could up and leave at their pleasure’, and whose employees tend not to be in trade unions, and are ‘often on insecure and ill-paid contracts’.11

More broadly, disempowerment is driven by the view that the working class used to be ‘the backbone of the country’, as a Labour switcher to Reform in Lancashire put it – but that today ‘you don’t get rewarded for a day of hard work’. The Progressive Policy Institute (PPI) reports that among working-class voters they polled, 59 per cent agreed that ‘You get less in return for working hard than a decade ago’. Only 12 per cent disagreed.12 By the time the cost-of-living crisis began to bite in 2022, pay had already been stagnant for 14 years.

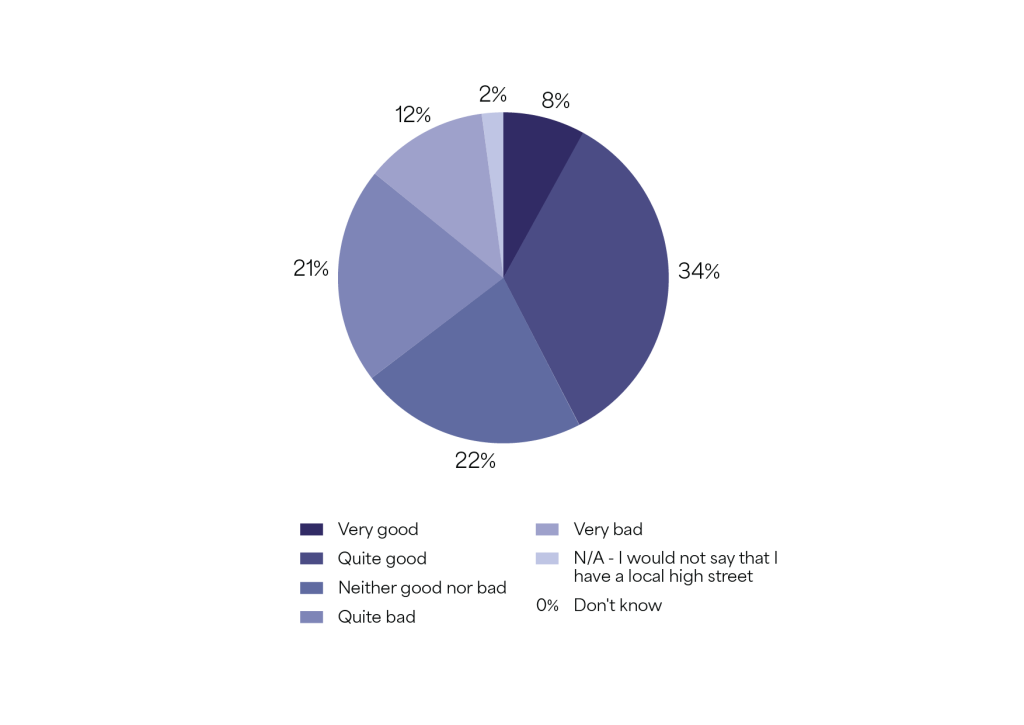

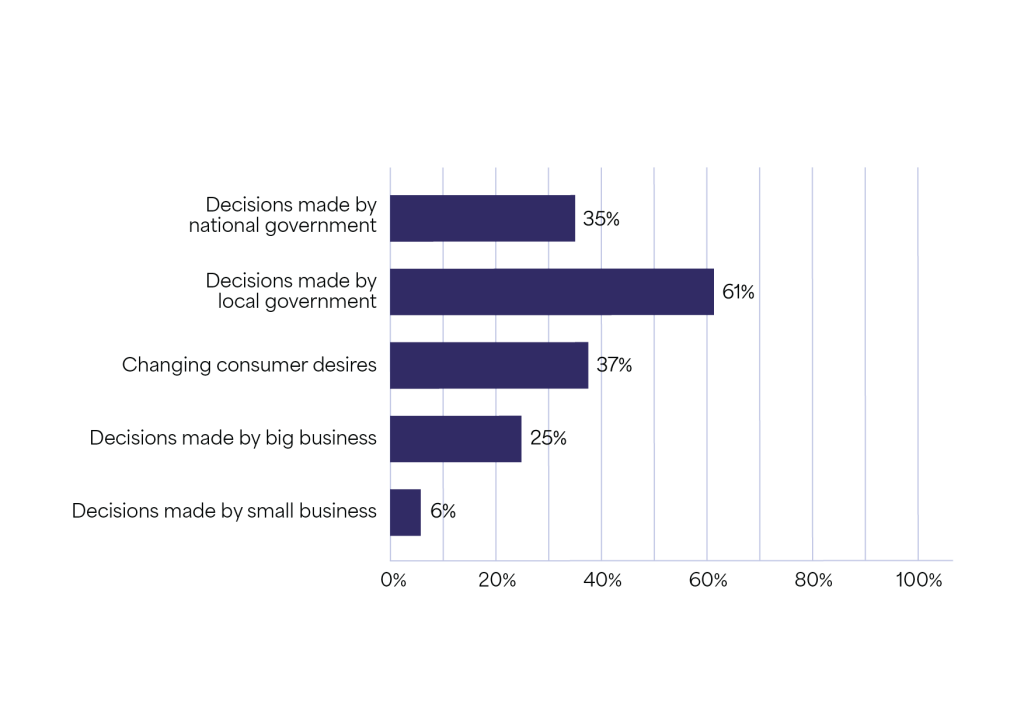

One image pollsters found coming up time and again, bringing all these disempowerments together, is the dying high street. Where once there were GP practices, pubs and cherished shops, now there are vacant lots – and nail bars, vape shops and barbershops, which some suspect of being fronts for organised crime.13 In many parts of the country, this has further exacerbated the spatial decline accelerated by the austerity-driven closure of libraries, youth spaces, Sure Start and leisure centres. One recent study by Power to Change suggests that such sustained losses correlate with increasing support for Reform UK.14

High street shops are also plagued by shoplifting, whether driven by poverty or the opportunities opened up for orchestrated looting by shop workers’ lack of confidence that anyone will turn up if they challenge this criminality and need to call the police. As the Labour minister Kirsty McNeill puts it, if the government:

‘made interventions which drove up pay and brought bills down, but people’s high streets were still terrible, and they still – when they went into their local Co-op – saw hard-working staff just absolutely besieged by shoplifting, and felt “there’s absolutely nowhere nice I can go and celebrate my kid’s eighteenth or last day of school, but I’m absolutely beset with nail bars and so on” – I don’t think we’d have succeeded.’

So if the public feels disempowered, who does have – or should have – power?

To many voters, politicians have quite enough power, but fail to use it as they should. Eighty per cent of British people tend to think ‘politicians don’t care about people like them’; 88 per cent of those who describe themselves as ‘financially struggling’ take that view.15 More in Common found that ‘Over half the public say that the challenges facing the UK require straightforward action. Those who already have the lowest level of faith in politics and are the most politically disengaged are the most likely to feel this way. This means that the public attribute the inability of politicians to implement common sense solutions to ignorance, incompetence, and indifference, rather than forces outside of political control.’16

In long-term fieldwork conducted in the post-industrial towns of Mansfield and Corby, the sociologist Sacha Hilhorst found that many of the people she interviewed ‘understood politics primarily through the frame of corruption’. They felt that in the past, politicians reciprocated voters’ trust by showing that they cared – by delivering local amenities, for example. But now, in these voters’ view, politicians took their votes, and constituents received far less in return than they used to. The idea that today’s politicians are literally corrupt is a serious and generally very unfair accusation,17 but it is evidently sincerely felt; Hilhorst interprets it as a way to make sense of the ‘abuse of entrusted power’.18

To other voters, politicians are impotent, unable to deliver on their own promises to ‘stop the boats’, for instance. They see nimble, audacious tech companies delivering wonders, while huge government departments struggle with core tasks like building and fixing infrastructure, and cutting NHS waiting times. As More in Common notes, ‘The perception that the government is powerless to respond to these basic expectations is driving disillusionment’.

Paradoxically, therefore, politicians seem at once powerful and powerless. Many see them as ‘at best, weak and incompetent, trapped in failing systems, at worst, wilfully propping up the status quo’.19 This feeds the sense of unfairness that underlies much of the discontent: that those in power are helping the wrong people. The public are desperate for change, but despair that it will ever happen. After so many let-downs, a politician’s promise is seen as a trick.

But if politicians are the public’s primary villains, they are not alone. The public also detects other powerful forces, whom politicians are failing to use their power to stop. These include those who disempower the public not as citizens, but as customers and employees.

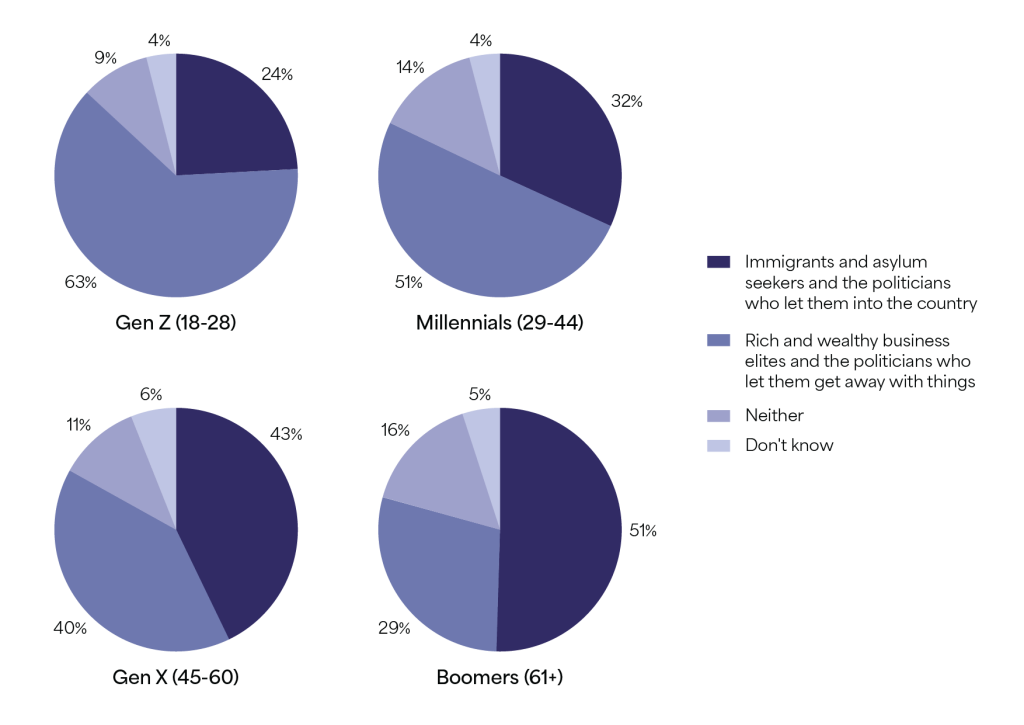

On this theme, polling conducted for this paper by Dynata in August 2025 suggested a striking generational split.20 We asked respondents to choose which of two groups they think is ‘most to blame for the problems in Britain today’: either ‘Immigrants and asylum seekers and the politicians who let them into the country’, or ‘Rich and wealthy business elites and the politicians who let them get away with things’.

Those aged 45 and over tended to blame immigrants and asylum seekers: 43 per cent of those aged 45-60 and 51 per cent of those aged 61 and over picked this option. By contrast, those under 45 tended to blame wealthy elites. This was the choice of 51 per cent of those aged 29-44, and 63 per cent of those aged 18-28.

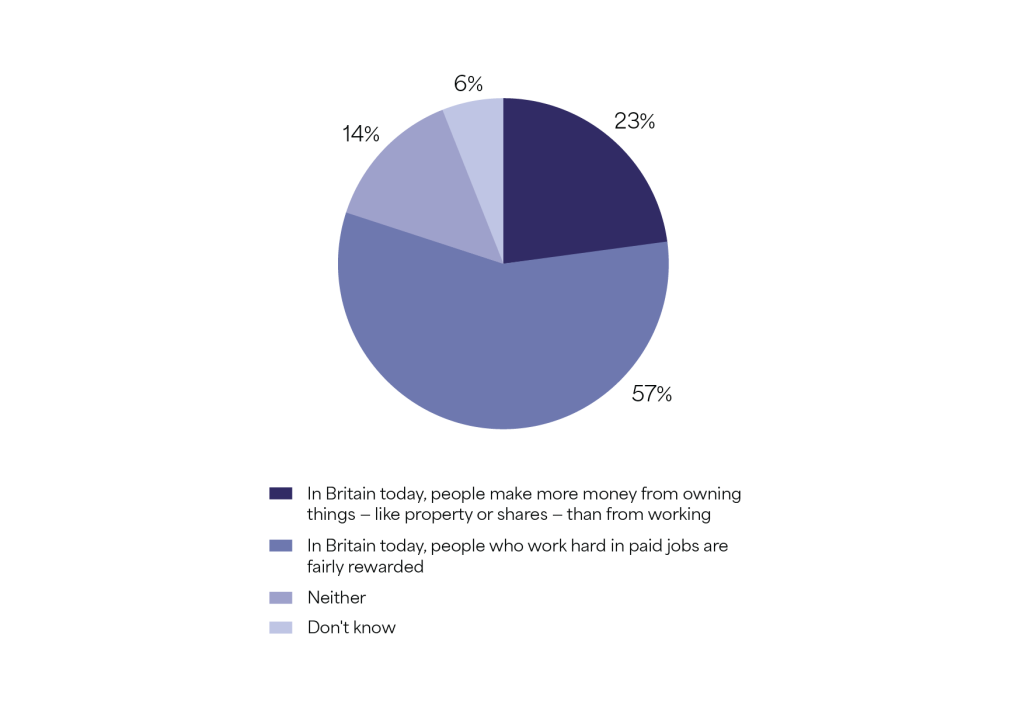

Asked whether ‘people who work hard in paid jobs are fairly rewarded’, or whether ‘people make more money from owning things – like property and shares – than from working’, 57 per cent of all respondents picked the latter option.

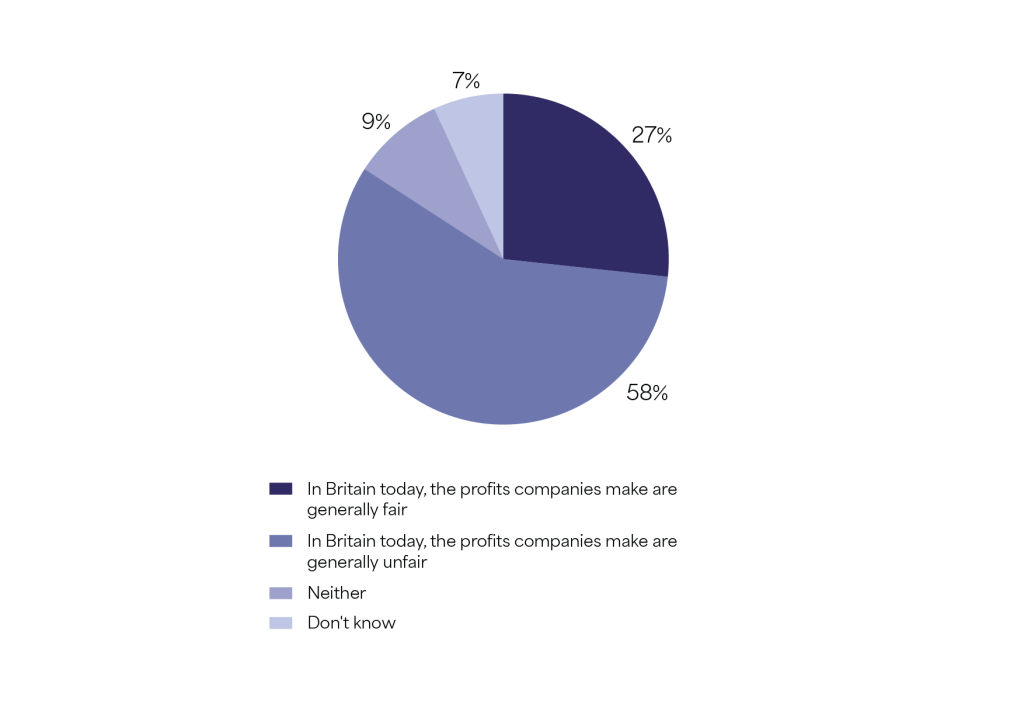

Similarly, 56 per cent thought ‘the profits companies make are generally unfair’.

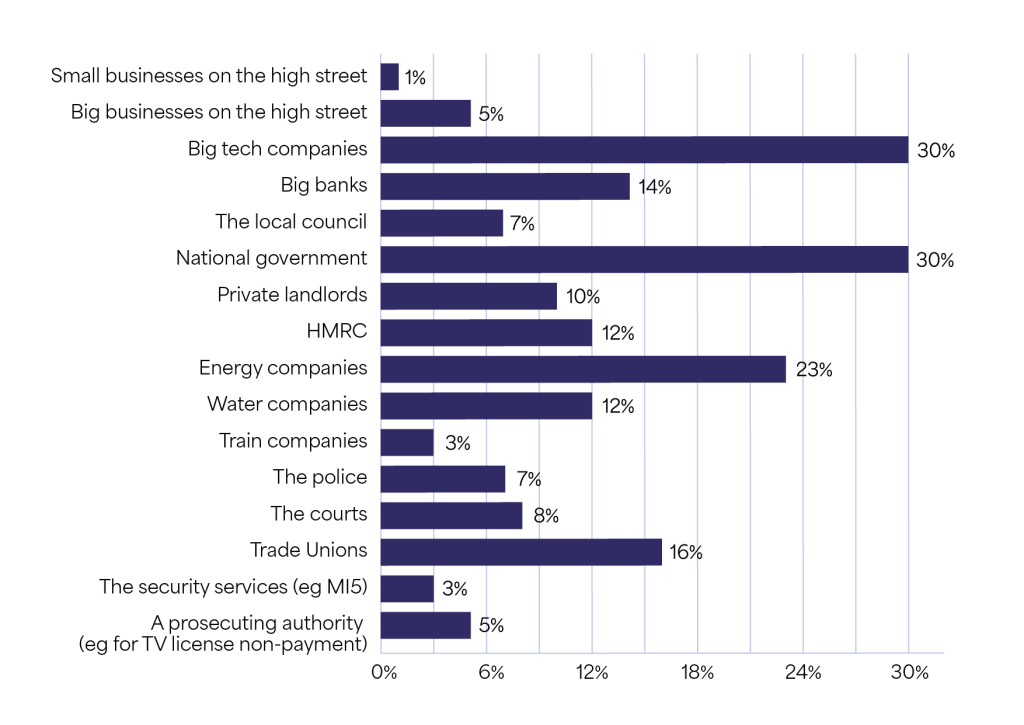

And when asked which groups in society had too much power, big tech companies scored equal highest with national government (30 per cent); in second place were energy companies (23 per cent).

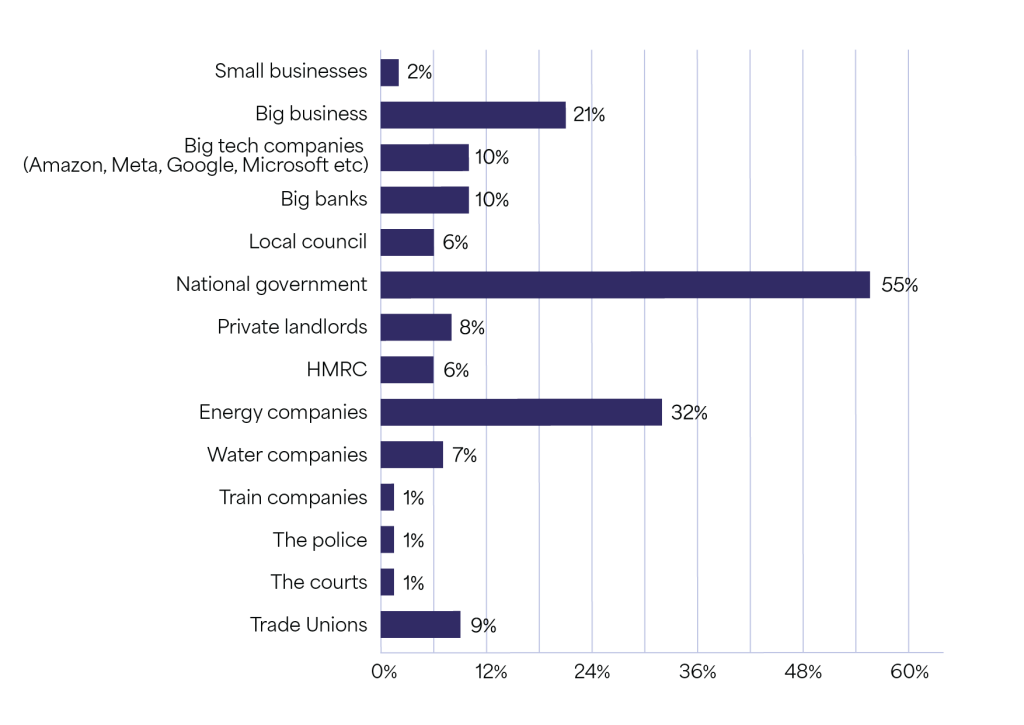

However, if the public does sense that forces other than government are partly responsible for their troubles, these are harder to see clearly. Throughout the survey, there is a consistent pattern of aiming blame primarily at national government. When asked who they held responsible for the cost of living – other than national government (55 per cent) – blame was quite widely diffused. Thirty-two per cent blamed energy companies, 21 per cent blamed big business, and 10 per cent apiece blamed big tech and big banks.

One way of reading this is that people do not have a clear sense of who is really responsible for prices and other economic decision-making, with the exception of the energy companies, so they default to blaming government, on the grounds that it has, or should have, the power to intervene.

Likewise, the groups that attract most blame in recent research, other than politicians, are businesses and, to a degree, the wealthy. This is not entirely surprising: by 2016, income inequality had ‘reached a level considerably above where it was in the early 1990s’.21 PPI reports that the voters they spoke to in the UK (and the US and Germany) ‘feel they are being taken for a ride by “greedy corporates” who are raising prices opportunistically’.22 The 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer Global Report finds that 64 per cent of UK respondents believe business leaders ‘purposely mislead people by saying things they know are false or gross exaggerations’, up 12 per cent on 2021,23 though it also found that business was seen as competent and ethical.24

The ‘rich’ occupy a similar role in the public’s view of how power functions. Edelman found that 60 per cent of respondents thought ‘The wealthy’s selfishness causes many of our problems’, and 68 per cent that ‘the wealthy don’t pay their fair share of taxes’.25 More in Common found that ‘The segments which most distrust business often take the same view towards the ultra-wealthy’, with many ‘feeling that the rich do not pay their fair share’.26 No wonder that there are widespread objections to the gap between rich and poor27 and that 70 per cent of Britons would prefer an economic system where that gap shrank, ‘even if people are less wealthy overall’.28 Perhaps one reason government is so unpopular is that it is seen by many as following policies that benefit big business (by 39 per cent) and the ultra-wealthy (by 52 per cent).29

As the cultural thinker Suzanne Alleyne has written, disempowerment – ‘the daily, perpetual frustrations of moving nowhere despite your best efforts’ – is physically exhausting. But it also feeds a theory of power, as the disempowered person becomes ‘stuck in a system that feels rigged against them’.30 More in Common reports that many voters believe ‘the rich and powerful play by a different set of rules to ordinary people’, which chimes with the widespread feeling that hard work is no longer rewarded.31

This sense of ‘one rule for them, another for us’ (or, more specifically, ‘lots of rules for us, very few for them’) is connected to another high profile political issue: the sense that those arriving on small boats are ‘jumping the queue’.32 PPI reports that working class and lower middle class voters ‘strongly believe that others benefit by not playing by the rules – whether illegal migrants or rich bosses’.33 One of Hilhorst’s interviewees talked of reading that a politician’s cousin was ‘the owner of this pharmaceutical company’ who had ‘been awarded contracts worth billions because of this pandemic’. One interviewee for More in Common’s ‘Shattered Britain’ report thought ‘the contracts and the procurement was all blatantly, blatantly just lads helping the other lads from the public school’.34 No wonder that, according to More in Common polling in April 2025, ‘The overwhelming majority of Britons (74 percent) think that the system is rigged to serve the rich and influential.’

In a survey of ‘Farage-adjacent TikTok’, the political economist Will Davies found it suffused with ‘the idea of the “scam”, of which government, politicians, asylum seekers and big business are all equally guilty’:

‘Government raises taxes on the pretence that it will look after people, but instead “wastes” it through inefficiency or misappropriation. Businesses keep on hiking prices, in ways that suggest something fishy is going on. One TikTok video shows a man comparing how much a toilet roll costs in the supermarket to how much it costs when bought in bulk: clear evidence of a scam.’35

Similarly, the pollster James Kanagasooriam suggests that both business and politics have developed a reliance on ‘shrouded attributes’: flashy short-term promises with a long-term downside, which they hope we won’t notice.36

Even from those who don’t see scams everywhere, there is a widespread demand for politicians to use their power to transform the country. According to More in Common, ‘seven in ten people said the General Election gave Keir Starmer a mandate to radically change Britain’.37 As FGF’s ‘In Power 01: Transforming Downing Street’ notes, this is the fourth attempt in the last decade to tap into ‘genuine and powerfully felt concerns that what the country needs above all is change – from the Vote Leave and Leave.UK campaigns in 2016, to Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party in the 2017 General Election, [to] Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party in 2019’.38 Labour now urgently needs to show voters that change is coming.

The frustration this breeds is particularly tangible among the young, including newly elected Labour MPs. This is visible in the rapid emergence of groups demanding the removal of barriers that impede state power, whether to drive growth, build infrastructure, or secure the border.

At present, too many mainstream politicians appear to lack the confidence to try to change how people think. Instead of being honest about unavoidable trade-offs, then persuading voters to support explicitly political choices by framing them in a compelling story of what has gone wrong and what it will cost to put it right, they get stuck in a trap. They end up merely explaining the difficulty of getting things done, which corrodes public trust and makes getting things done more difficult still.

Labour in particular has a longstanding tendency to take office seeing itself as a tenant in the corridors of power. In the throes of financial crisis in 1931, the Labour government strove desperately to stave off the unthinkable: coming off the gold standard. Chancellor Philip Snowden was convinced this would mean ‘irretrievable disaster’: the pound would slump in value, inflation would soar, and Britain would see ‘the destruction of the social services and the reduction of the standard of life for a generation’.39 The government split, and fell.

Yet within weeks, the new national government was forced off gold – and neither the pound nor the economy fell to ruin. The pound dropped somewhat in value, allowing interest rates to ease, releasing a years-long housing construction boom, and the economy actually lifted. One of Labour’s ousted Cabinet Ministers was left lamenting: ‘No one ever told us we could do that.’40

To make changes that will re-empower people, politicians need to identify what is disempowering the public – and the state, in its attempts to improve people’s lives.

Perhaps one reason politicians are so stuck is that that they are too accepting of the public’s theory of power. If they go along with the idea that they themselves – MPs and ministers and their civil servants – are to blame for the public’s disempowerment, then the logical solution is to get rid of politicians and Whitehall and try something else.

Instead, democratic politicians need to challenge the claim that the state is irreducibly useless and/or self-serving. The public’s theory of power starts with real frustration and accurate information but ends up heading, with the help of myth, misinformation and extremist goading, towards unnecessarily extreme measures. So how might genuine frustration be channelled towards genuine solutions? In this, the public’s theory of power could be made more of a partner than it might seem.

As we’ve seen, the public also sees other powerful forces as a problem – it just tends to default back to blaming the state. This may be because government is so much more visible than other forces. Or because the idea that the state is fundamentally malignant is so entrenched. Or maybe (as seen in our polling) because people tacitly believe the state does have power, but it is failing to put it to good use.

In our poll, when asked to assess the power of the British state today, 50 per cent of respondents said it had ‘too much’; only 18 per cent said ‘too little’. One way of reading this is that the state is simply over-powerful; another is that given its failure to deliver, it has power it is not putting to good use – but power nonetheless.

For there is a telling discrepancy in how the public allocates blame. As PPI notes, ‘these voters all strongly believe that it is not just politicians who “benefit by not playing by the rules”’ (emphasis added). Yet, crucially, ‘much of their ire is directed to politicians of all parties’.41 British Future reports a similar finding.42 This tendency is reinforced by media coverage which often appears much keener to blame the state and politicians than any other powerful force in society, with the possible exception of the water companies. One comment piece for The Times drawing on some of this polling was headlined ‘We’ve become a low trust society – the state must step up’.43 So it must, but it cannot do it alone, and nor is it tenable, or politically strategic, for the state to take all the blame.

In the Ipsos Veracity Index, it is striking that – with the glaring exception of politicians – public sector roles generally rank higher than those in the private sector. Nurses, doctors, teachers, professors, museum curators, judges, police, civil servants are all in the top half; bankers, estate agents, business leaders, private landlords, advertising executives are all in the bottom half.44

Perhaps, therefore, it would be possible to build on existing public perceptions, but then refocus how the public sees how power works – that politicians are not to blame for everything, and that they are trying to make people’s lives better, but that, as we’ll see, their power has been diffused beyond their reach and entangled in complexity, while other forces and ideas stand in their way.

This will require identifying, challenging and overcoming some deeply entrenched ideas – but here, politicians and the political media could learn something from the public. As the pollster Steve Akehurst of Persuasion UK observes, ‘the theatre of “public opinion”’ is often ‘just a drama for elites’. Many of the constraints in which politicians entangle themselves are old norms, folk memories and taboos:

‘There are just lots of areas where elites basically hem themselves in for reasons to do with received wisdom among elites … you can see how the system perpetuates itself, because, it will, in the short term, punish anyone that steps outside of those norms. And therefore, as a politician, you need to be brave enough to walk through that storm.’

As he suggests, this has been exposed in the United States by Donald Trump, who has successfully ‘trespassed across all of those norms and exposed them precisely for what they are, which is fictions, basically’.

As PPI puts it, working-class voters often ‘concede that the parties and candidates on the populist right may not have all the answers’, but things are broken and mainstream parties ‘can’t or won’t fix things’, so the prospect of a populist government that ‘will shake things up’ is ‘a risk worth taking’.45

Other politicians such as Franklin Roosevelt and Margaret Thatcher have achieved radical change, without trashing liberal democracy – instead restoring its credibility after years of crisis. But it meant overcoming entrenched ideas and the concentrations of power those ideas enforced, by defining the bounds of the ‘possible’.

As the then newly-elected Labour MP Josh Simons put it in September 2024, drawing on his experience of defeating a strong challenge from Reform: ‘We’re too quick to say “we have to do X, because bankers, economists, lawyers told us so”. Voters think, “What’s the point of voting for people who are told what to do?”’46

To avoid a future that makes the public’s theory of power a reality, which blames politicians for everything and lets other powerful forces off scot free, politicians will need to ask themselves why the state is seen as irreducibly useless, and democratically-elected representatives are so distrusted. Then they will need to overcome the fears and taboos that hold these ideas in place. The stakes could hardly be higher.